Student protests and activism has boomed on the UNB campus in the past year. Last year, protests began in response to the ongoing genocide in Palestine. Several major pro-Palestine groups engaged, and continue to engage, in peaceful, well ordered, and effective protests both on the UNB campus and at various government buildings in Fredericton. More recently, the Student Organizing Collective has continued these protests and expanded the scope of student activism at UNB.

These groups are part of a long history of activism and protest at UNB. It is easy to mistake pro-Palestine protests as a new feature on the UNB landscape, but both the UNB Administrators (President’s Office, Board of Governors, Faculty Deans, etc.) and native Frederictonians know that protests are not a new occurrence on College Hill. In fact, pro-Palestine activism has occurred at UNB for at least twenty years.

The characterization of these protests as new and disruptive is deliberate. Because an average undergraduate degree only lasts four years, the UNB Admins know that they can simply keep quiet and wait until this newest generation of student protestors graduate. The result is a view of UNB’s history that often obscures student protests, generally characterizing them as inconsistent and childish.

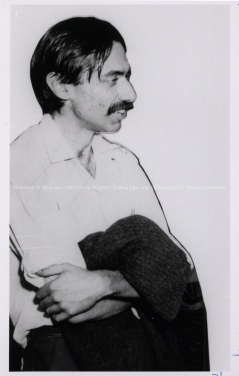

Most UNB students and alumni “in the know” about protests at UNB have no doubt heard of the Strax Affair. UNB’s most famous and well covered student protest occurred in the fall of 1968. The exact reasons for the Strax Affair appear pedantic or overblown. But the Strax Affair is not an isolated event, instead it helps to illuminate the nature of UNB and its reaction to student activists.

In September 1968, UNB physics professors Norman Strax and a group of students protested the introduction of student photo identification. Strax and his compatriots (variably dubbed CSDS, SDS- Mobilization, and later Liberation 130) attempted to sign books out of the Harriet Irving Library—a process that as of Fall 1968 required students and faculty to present their ID. When asked for their ID, they refused. Over 300 books piled up at the circulation desk and the HIL closed early. Strax and SDS-Mobilization repeated this protest twice more. For his involvement in what was later dubbed the “Bookie-Book” protest, Strax was effectively fired (Footnote 1)

Many reports on the Strax Affair focus on the aftermath of the Bookie-Book protest (a 40 day occupation of Strax’s office, major picketing in front of Sir Howard Douglas Hall, and the UNB President resigning). Strax’s legal battle with the UNB Admins over his wrongful dismissal dominates narratives surrounding the Affair. However, at the center of the Affair is a group of UNB students and faculty resisting the increasing corporatization of UNB.

UNB is funded by the public. Every year UNB receives money from the Province of New Brunswick to continue running (approximately 46% of its operating budget in 2024-25) (Footnote 2). The Province benefits by maintaining the crowning jewel of their capital city, and UNB benefits by receiving money for free. But the money the Province gives to UNB is taken from the New Brunswick tax pool. In the past, UNB provided simple services to those tax payers—under the assumption that UNB was a publicly funded institution not a private corporation. The implementation of photo IDs meant that campus security now had a precedent for removing the public from UNB property—property they paid for (Footnote 3).

The point is that Strax and SDS-Mobilization were not protesting photo IDs because they did not want their picture taken. They were protesting a symbol of the UNB Adminstration’s indifference to the people they are supposed to serve. They were protesting UNB taking your money and not giving you a say in how it is spent—such as funding an ongoing genocide.The Strax Affair is not the beginning nor the end of student protests at UNB.

More recently, students in the early 2000s protested the various wars in the Middle East (Iraq, Afghanistan, etc.) as well as the Israeli occupation of Palestine. The joint STU and UNB Social Justice Society functioned as a loose network of these activist students throughout the early 2000s. In the 1940s students boycotted racist barbershops in Downtown Fredericton that refused to cut Black people’s hair. In the early 2010s a group called STRAX once again protested Israeli occupation of Palestine. STRAX also successfully protested police, military, and Lockheed-Martin recruitment on the UNB campus—a tradition carried on by the Student Organizing Collective.

The point is that the Student Organizing Collective is not new. The Student Organizing Collective has existed at UNB for decades—even if they do not realize it. In four years the Student Organizing Collective will still exist—possibly under a new name. The UNB Admins will do everything in their power to help you forget these protests. Furthermore, there are no doubt many more protests that I do not know about—protests that were successfully forgotten.

The bottom line is that you do not need to run out to the picket line to make a difference in this long history of student protest, all you need to do is remember!

Footnotes:

1. Technically Strax was suspended without cause (i.e. there was no reason given for his suspension and no formal warnings). After Strax ignored the suspension UNB President Colin Mackay filed a court injunction against Strax barring him from entering campus, effectively ending his career at UNB. In 1970, after the Strax Affair, Strax applied for his old job back but received no reply from then UNB President James Dineen. Sourced from the UNB Archives & Special Collections, “Strax Case,” UA RG 127.

2. University of New Brunswick, 2024-25 Operating Budget, https://www.unb.ca/finance/_assets/documents/rpb/2024-25-budget.pdf.

3. According to The Brunswickan archives there was at least one confirmed report of Campus Security removing an individual from the UNB campus when they refused to present an ID card., see: John White, “Security Tightens, UNB Adopts All-Purpose ID Cards,” The Brunswickan (Fredericton, NB), Sep 12, 1968.

Op-Ed Submission: October 12th, 2024