Imagine a world of birds; birds with gaping, hungry bills, and souls simply trying to live being devoured in droves. You may picture the fantastical seabound world of The Boy and the Heron, or you may see the real world as we know it. Regardless of what you see, you may ask yourself: do the souls …

The Boy and the Heron: Film Review

Imagine a world of birds; birds with gaping, hungry bills, and souls simply trying to live being devoured in droves. You may picture the fantastical seabound world of The Boy and the Heron, or you may see the real world as we know it. Regardless of what you see, you may ask yourself: do the souls choose to live? Do the birds choose to eat? Maybe not, but they do. What is so beautiful about that? What was dubbed Miyazaki’s last film explores the beauty in the everyday, the chaotic, and that which we cannot control: in other words, life itself.

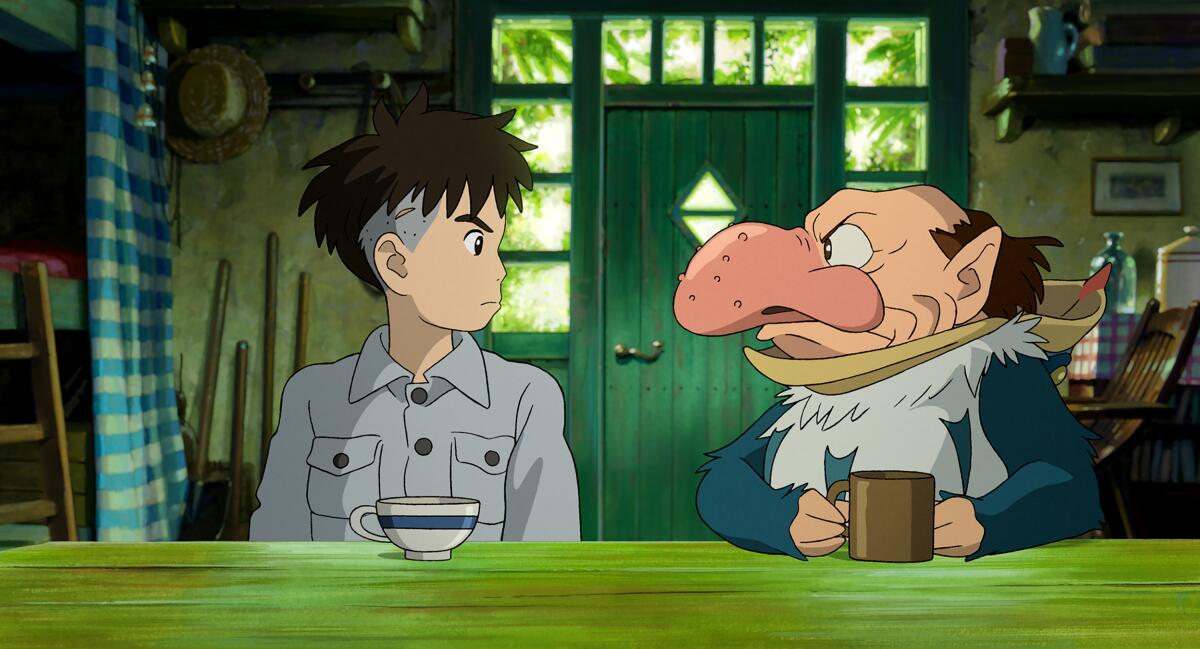

Hayao Miyazaki’s 2023 film The Boy and the Heron blends World War II Japan with perhaps the grandest of Ghibli’s secondary worlds, brilliantly connected to our own. After Mahito Maki’s mother dies in a bombing-caused hospital fire, his father moves them to their countryside estate, where he remarries Mahito’s aunt, Natsuko. The opening half of the film is of a fitting slower pace, meticulously carving the experience of adjustment and grief for Mahito whilst penetrating a war torn reality with wondrous chaos that represents the absurdity and chaos of that very reality.

As Mahito battles grief and nightmares of his mother’s death – integrated into the narrative with sporadic, flowing linework of movement, disorientation, and flame – he is tormented by the local grey heron. An absurdly proportioned human nose and teeth protrude from the heron’s mouth (like later, other birds), symbolizing the dark human realities reaching straight from the throat of fantasy.

The heron’s mocking, scheming, and beguiling marks his position as the boy’s “guide” through the strange world and a mirror of the never-certain truths and challenges of life. This eerie distrust in the characterization of the heron portrays the questionability of human desire, relationships, and our trust in life and the world itself. The heron continues by luring the boy into a fantasy world, an embodiment of the escapism sought by Mohito from a hatred of daily life — the pointless monotony amidst the horrors of existence. He carries this scar throughout the film, literally ingrained in the side of his head after self-harming to escape school and the grueling pressures of the day-to-day.

This being said, even the fantasy world is fragile and filled with the flaws of life. We return to the birds. The falsity of freedom permeates the existence of this world, and even the existence of its inhabitants.

One dying pelican croaks, “We didn’t choose this life,” as, says the film, nobody does. Though it dies gruesomely, Mahito, the heron, and we, the audience understand and respect that life and loss.

Though the birds want to consume you, though life wants to consume you – as frogs, pelicans, and parakeets engulf Mahito time and time again — life has value. Breaking through the swarms of life is merely part of the journey to find that value.

Forces in this world want to keep Mohito there, flapping in like abrasive birds to keep him from reality and in the crumbling fantasy. However, through experiencing this world — crawling with these flawed, beautiful, horrifying creatures — Mohito sees life. Pelicans soar like warplanes, while Mohito’s warplane craftsman father searches tirelessly for his missing family. The Boy and the Heron presents the warped sense of morality that exists within all of us as a result of the world we live in. It tells us that despite life’s flaws and absurdities, it is worth living, and everyone discovers what it means to live in different ways.

The film’s visual imagery, from things crumbling into pieces, to creatures swarming over you, to grievances haunting you (the burning street or the pesky bird), writhes with death and decay.

The fantasy world sings the reality that yes, everyone will die, everything will turn to dust, and yet, the vibrant colour of the now (gardens both rural and like paradise, vast oceans, and those very same parakeets) bring life to life. Life is not death; death is part of life. Mahito is tasked with taking control, to see these creatures and both reality and unreality for what they truly are. His quest into the fantastic world is not merely to save the captured Natsuko, but to heal his understanding of the world of his own.

Alive through its absurd and metaphorical visual storytelling, The Boy and the Heron juxtaposes life and death as a blessing and a curse — it just may take a journey to see the beauty in the chaos.

Daniel S. Burton

Keep in touch with our news & offers

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Thank you for subscribing to the newsletter.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please try again later.