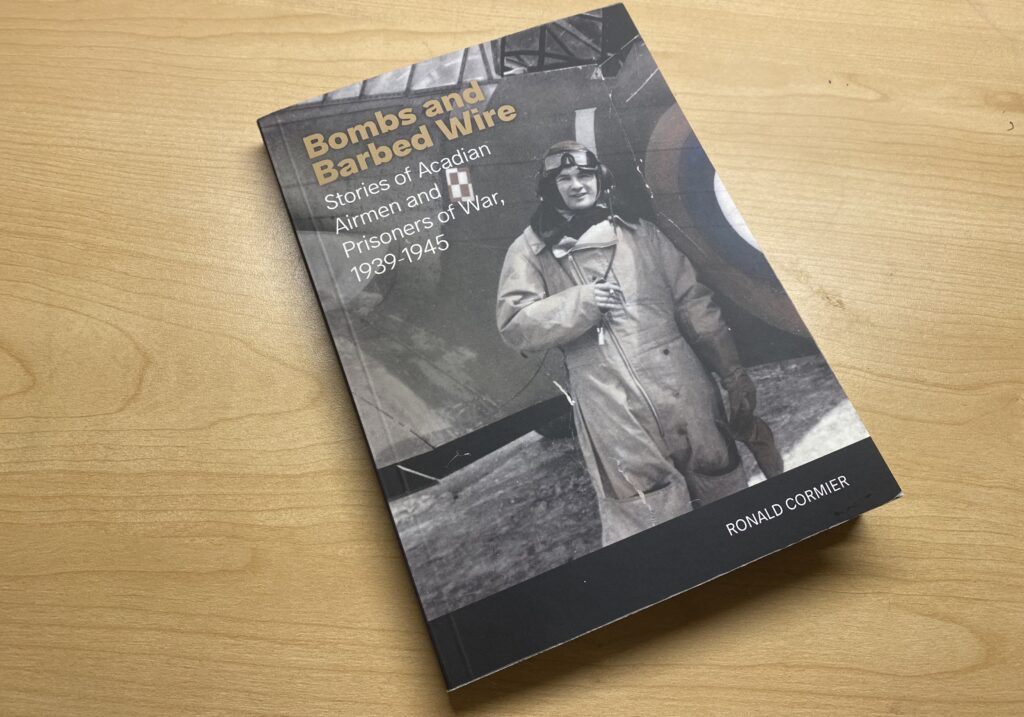

Ronald Cormier’s Bombs and Barbed Wire tells the stories of Acadian servicemen during the Second World War. It is the English-language version of Cormier’s earlier Entre Bombes et Barbelées, which was published in the nineties.

The book is being released in a partnership between Goose Lane Editions and the University of New Brunswick’s Gregg Centre, integrating the New Brunswick Military Heritage Series. Cormier derives his material from extensive interviews with ten Acadian veterans, which were conducted between 1989 and 1990.

Interesting and accessible, Bombs and Barbed Wire is a must-read for those with a penchant for military history, especially New Brunswick military history.

The interviews constitute the bulk of the book, except for the chapter on Dubé. Cormier does provide, however, contextualization to the stories of the servicemen. He weaves their first-hand accounts with landmarks of the war.

Narratives of battles, maps that signal the journeys of the particular soldiers, and photographs, are all utilized by Cormier. These devices help the reader to both make sense of the particular journeys of the Acadian servicemen as individuals and see how they are embedded in the landscape of the Second World War. Nevertheless, the testimonies remain central — the war is the background.

It is fascinating to have a glimpse of the inner worlds of the servicemen as they confront the landscape of the war — as individuals and as a collective. The stories of these men often come together, briefly or otherwise, before parting ways once again. Cormier covers, across two different chapters, the experiences of Prisoners of War (POWs) who were kept captive in the same camp, Stalag-VIIa. Their names were Alcide Gallant and Armand Landry, and although it is unclear whether the two could have met in the midst of a large number of Canadian POWs, their stories have common themes. For example, both of them report having seen the concentration camp of Dachau. They also make remarks on the conditions of life in the camp, the labour they performed, and the coping mechanisms employed in such a hostile environment.

There is a scarce use of footnotes in Bombs and Barbed Wire. While this may ring like a problem to professional and in-training historians, it is worth considering its intended audience of Cormier. Bombs and Barbed Wire is closer to a popular history book, hoping to reach audiences way beyond academia. This conclusion can be reached for two reasons: first, it aims at shining light on the stories of Acadian servicemen — giving emphasis to the collective (public) memory of the Second World War. Second, it is very accessible in its language. This accessibility is perhaps one of the book’s greatest strengths.

On the other hand, Bombs and Barbed Wire often rings as propagandistic. In the introductory chapter, Cormier draws a direct line between past and present. He claims that Canada’s relative prosperity is owed to “the more than one million men and women who sacrificed their youth to fight tyranny.”

In the acknowledgements, he emphasizes that “it is as heroes that we must remember them in our collective memory.” The narratives embedded in these claims demand a certain level of nuance and caution. One may suggest, tentatively, that it is simply as men that they must be remembered.

The book itself, in its strongest points, emphasizes the human aspect of the servicemen: their turmoil, their coping, their decisions, and their trauma.