In 1991, a fringe political party running on an anti-bilingualism platform became the official opposition in New Brunswick. francophone New Brunswickers are not likely to forget Blaine Higgs’s 1989 leadership bid for the now-defunct Confederation of Regions Party, a political protest party whose core policy was eliminating official bilingualism.

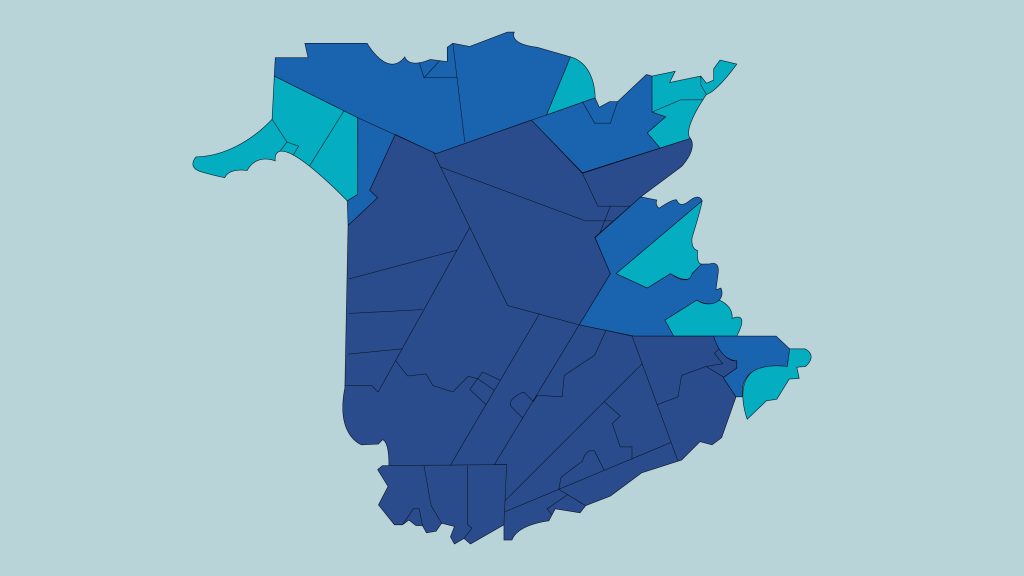

The 2020 New Brunswick General Election map shows political divides are still alive between French and English ridings. While Higgs won a majority, thanks to his success in primarily anglophone ridings, he is still trying to distance himself from the discriminatory political views he held 30 years ago.

“I have a different perspective on things today… I believe that all New Brunswickers, French and English, have the opportunity to speak their own language and to learn another one. My opinion has changed over the last 30 years,” Higgs said in the lead up to the 2018 New Brunswick General election.

While many have long forgotten the Confederation of Regions Party, its legacy ripples through New Brunswick politics. Originating as a federal party, CoR sought to abolish Canada’s official bilingualism and split the Canadian provinces into four self-governing regions. The party found its only success amid language-based tensions in New Brunswick.

After Frank McKenna’s win against Richard Hatfield in the 1987 election, many New Brunswick Conservatives, unhappy with new regulations designating certain provincial jobs as bilingual, defected to the New Brunswick Confederation of Regions Party. CoR drew in supporters from across the province, many who would not identify as right-wing, rallying around the cause of making New Brunswick an English-only province.

The success of CoR in New Brunswick is only one instance in a long history of anti-francophone sentiments found in the province. Parallels can easily be drawn with another third party, People’s Alliance, that runs on a campaign promising common sense but primarily finds support with anti-bilingualism rhetoric. Comments from 1991, when CoR elected 8 MLA’s and became the official opposition, can remind us of the dangerous potential of populist political movements.

“Assimilation is not a bad word in my book. My people did it—they used to speak Gaelic,” said CoR MLA David Hargrove in an interview for Maclean’s magazine shortly after the 1991 election.

CoR found less success federally. The unpopular proposal to combine the provinces into four regional jurisdictions was a hardline issue that most Canadians would not support. The party experienced additional controversy when in the 1988 federal election, the party’s candidate in Mississauga East, Ontario was Paul Fromm, an infamous white supremacist with connections to the KKK and neo-Nazi groups.

The New Brunswick CoR Party slowly fell apart as internal political divisions led to splits in support. Many members eventually defected back to the Conservative party, a move that was equally divisive within the Conservative Party. Following years of infighting, CoR’s numbers dwindled until it was officially dissolved on March 31, 2002.

With rising tensions regarding the availability of French language services and the hiring restrictions that come along with it, support anti-francophone rhetoric still strong in many anglophone ridings, and the success of CoR in 1991 shows us that this ideas hold the potential for further growth. Anti-francophone politics are not solely an issue of rural and urban division, the majority of CoR’s support centered around New Brunswick’s capital city, Fredericton.